HTTP status codes are short numeric messages sent by a website when someone tries to open a page. These codes help the browser or tool know if the request worked, failed, or needs a new step. Each code is just three digits, and every number tells something different.

For example, 200 means success and the page loaded fine. If you see 404, it means the page was not found. These codes are part of the web’s basic rules and help both people and machines understand how a site is doing behind the scenes.

What is the purpose of HTTP status codes

HTTP status codes help browsers and bots understand what happens after they request a web page. When a page loads correctly, the server sends a success code with the page content. If the page is missing or something breaks on the server, it returns an error code. These short, three-digit codes explain the outcome without needing custom rules for each website.

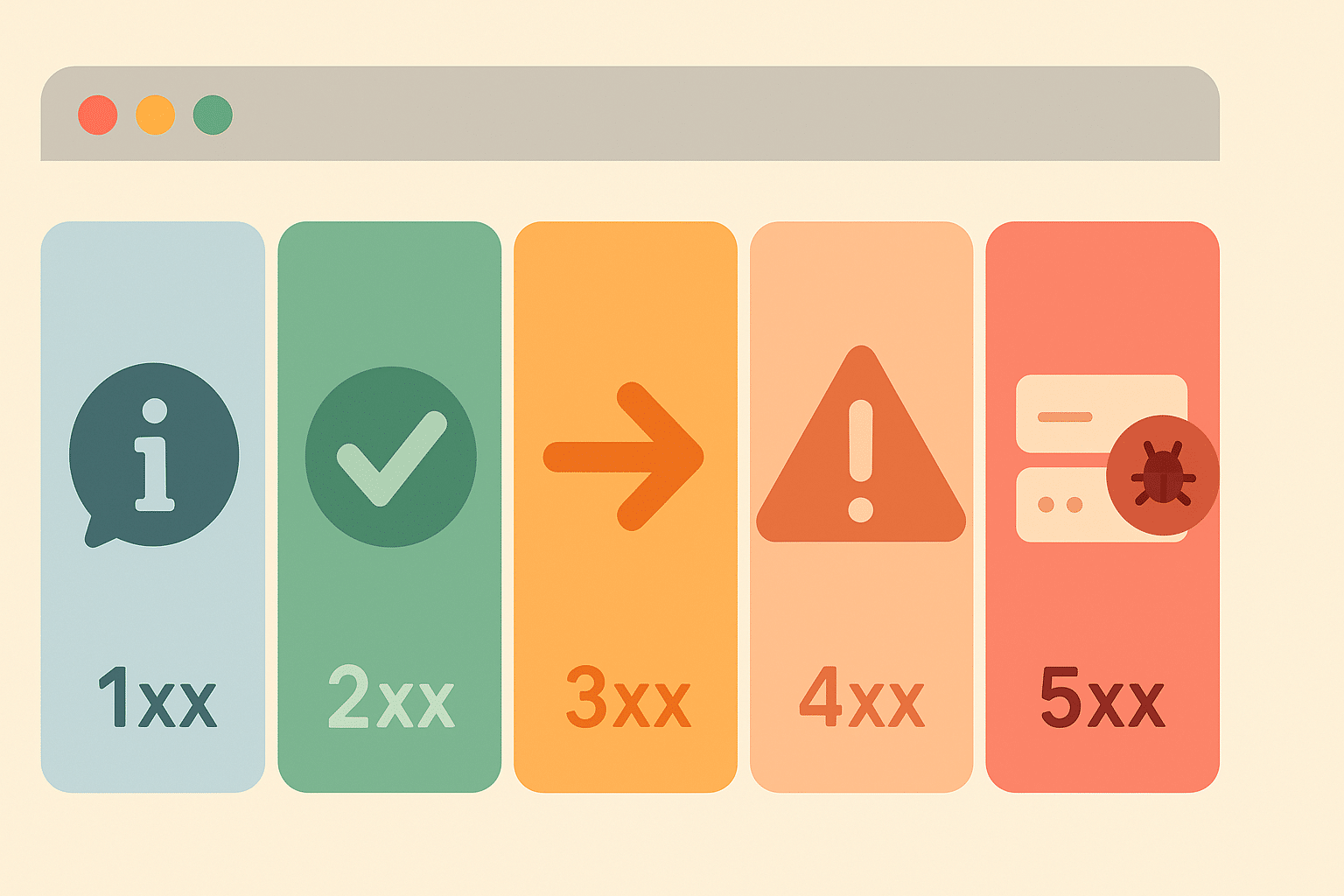

Types of HTTP Status Codes

| Class | Code Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1xx | 100–199 | Request received and understood; server is continuing the process. |

| 2xx | 200–299 | The request was successfully received, understood, and accepted. |

| 3xx | 300–399 | The client must take additional action to complete the request. |

| 4xx | 400–499 | The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled by the server. |

| 5xx | 500–599 | The server failed to fulfill a valid request due to internal problems. |

| Status Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1xx – Informational | Request received, continuing process |

| 100 | Continue |

| 101 | Switching Protocols |

| 102 | Processing (WebDAV) |

| 103 | Early Hints |

| 2xx – Success | The request was successfully received, understood, and accepted |

| 200 | OK |

| 201 | Created |

| 202 | Accepted |

| 203 | Non-Authoritative Information |

| 204 | No Content |

| 205 | Reset Content |

| 206 | Partial Content |

| 207 | Multi-Status (WebDAV) |

| 208 | Already Reported (WebDAV) |

| 226 | IM Used |

| 3xx – Redirection | Further action needs to be taken to complete the request |

| 300 | Multiple Choices |

| 301 | Moved Permanently |

| 302 | Found |

| 303 | See Other |

| 304 | Not Modified |

| 305 | Use Proxy (deprecated) |

| 306 | Switch Proxy (no longer used) |

| 307 | Temporary Redirect |

| 308 | Permanent Redirect |

| 4xx – Client errors | The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled |

| 400 | Bad Request |

| 401 | Unauthorized |

| 402 | Payment Required (experimental) |

| 403 | Forbidden |

| 404 | Not Found |

| 405 | Method Not Allowed |

| 406 | Not Acceptable |

| 407 | Proxy Authentication Required |

| 408 | Request Timeout |

| 409 | Conflict |

| 410 | Gone |

| 411 | Length Required |

| 412 | Precondition Failed |

| 413 | Payload Too Large |

| 414 | URI Too Long |

| 415 | Unsupported Media Type |

| 416 | Range Not Satisfiable |

| 417 | Expectation Failed |

| 418 | I’m a teapot (April Fools / Easter egg) |

| 421 | Misdirected Request |

| 422 | Unprocessable Content (WebDAV) |

| 423 | Locked (WebDAV) |

| 424 | Failed Dependency (WebDAV) |

| 425 | Too Early |

| 426 | Upgrade Required |

| 428 | Precondition Required |

| 429 | Too Many Requests |

| 431 | Request Header Fields Too Large |

| 451 | Unavailable For Legal Reasons |

| 5xx – Server errors | The server failed to fulfill a valid request |

| 500 | Internal Server Error |

| 501 | Not Implemented |

| 502 | Bad Gateway |

| 503 | Service Unavailable |

| 504 | Gateway Timeout |

| 505 | HTTP Version Not Supported |

| 506 | Variant Also Negotiates |

| 507 | Insufficient Storage (WebDAV) |

| 508 | Loop Detected (WebDAV) |

| 510 | Not Extended |

| 511 | Network Authentication Required |

Why Standard Codes Are Important

All browsers, crawlers, and tools follow the same status code meanings. This makes the internet easier to use and maintain. For example:

- 404 means not found, so the browser shows an error page

- 301 redirect tells the browser or search engine to go to a new link

- 500 codes point to server problems

Using the same set of codes avoids confusion. It means Googlebot or any browser can understand redirects, missing pages, or errors the same way, no matter which site they visit.

Function in Web Communication

These codes create a universal web language. A crawler knows when to reindex a page or drop it. A user sees clear feedback when something goes wrong. From loading a page to following a redirect, HTTP status codes keep browsers, users, and servers in sync.

What are the classes of HTTP status codes

HTTP status codes are grouped by their first digit into five main classes. Each class shows a broad meaning of what happened when a page was requested. This structure helps users and search engines quickly understand the type of response, even before looking at the full code.

Informational responses (1xx)

1xx codes mean the request was received, and the server is still working on it. These responses are not usually shown to users. One example is 100 Continue, which tells the browser to go ahead with the next part of the request.

Successful responses (2xx)

2xx codes confirm that the request worked. The most common one is 200 OK, which means the page loaded correctly. Other examples include:

- 201 Created – A new page or resource was made

- 204 No Content – The request worked, but there is nothing to show

These codes run quietly in the background when sites load as expected.

Redirection messages (3xx)

3xx codes tell the browser to look somewhere else. This class includes codes used for redirects, which help move traffic from old pages to new ones. For example:

- 301 Moved Permanently – The page has a new permanent web address

- 302 Found – A temporary move to another page

- 307 Temporary Redirect and 308 Permanent Redirect – Redirects that keep the request method the same

Search engines use these signals to update links and page paths.

Client error responses (4xx)

4xx codes show that something went wrong on the client side. This can happen if the user types the wrong URL or tries to view a page they cannot access. Examples include:

- 400 Bad Request – The request was unclear or broken

- 403 Forbidden – Access is blocked

- 404 Not Found – The page does not exist

- 410 Gone – The page is deleted and will not return

These are often seen when a link is broken or a page has been removed.

Server error responses (5xx)

5xx codes mean the server could not handle a proper request. These errors point to issues on the site itself. Common ones include:

- 500 Internal Server Error – A general issue on the server

- 502 Bad Gateway – One server got a wrong reply from another

- 503 Service Unavailable – The server is down or too busy

- 504 Gateway Timeout – The server took too long to reply

These are usually temporary and fixable by the site admin.

Real-world usage and visibility

There are over 60 official HTTP status codes, but only a few show up in normal web use. Most people see 200, 404, or 500, and never encounter less common ones like 102 or 207. Some codes are made for special tools, like WebDAV or proxy servers, and stay hidden from the user. Grouping the codes by class helps spot what kind of response happened at a glance—2xx means success, 4xx means a user-side error, and so on.

Notable HTTP Status Codes and Their Meaning

While many HTTP status codes exist, a few are more visible and widely used. These codes signal success, redirects, errors, or legal restrictions. Each one has a precise meaning that helps both users and machines respond the right way.

Common informational and success codes

- 100 Continue – The first part of a request is accepted, and the client can send the rest. This helps when sending large data by checking headers first.

- 200 OK – The most standard success code. It means the request worked, and the server is sending the content as expected.

Redirect codes used in web operations

- 301 Moved Permanently – This tells the browser that a page has a new permanent address. Search engines update their index and carry over ranking power.

- 302 Found – A temporary move to another page. It keeps the original URL for future use.

- 304 Not Modified – Returned when a page has not changed since the last visit. This saves bandwidth by allowing the browser to use its cached version.

Error codes for denied or missing pages

- 403 Forbidden – The server understands the request but will not allow it. Often used when access is blocked or a folder is not open to the public.

- 404 Not Found – The page does not exist. This is a common error when links break or pages are removed. Browsers show a “not found” screen, and search engines slowly remove the page from their index.

- 410 Gone – Similar to 404, but more exact. It says the page was once there but has been permanently removed. Google treats this much like a 404, but may drop it faster from results.

Server-side error codes

- 500 Internal Server Error – A general server error. It means something broke on the website’s backend. The problem could be code, configuration, or a system failure.

- 503 Service Unavailable – The server is temporarily down or too busy. This is often used during planned maintenance or short outages. It signals search engines to come back later.

Legal restriction status code

451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons – This means the page is blocked by law, such as due to a court order. The number 451 is a reference to Fahrenheit 451, a story about censorship. It shows that access is denied due to legal demands.

Why these codes matter

These notable HTTP status codes are used in everyday web work—especially 200, 301, 302, 404, 410, 500, and 503. Developers watch them closely. For example:

- Choosing 301 or 302 affects how links pass authority

- A 404 vs 410 changes how Google treats missing content

- A 503 helps protect site rankings during downtime

Understanding these codes helps improve site performance, SEO, and user experience.

How Status Codes Work

When a browser or bot sends a request to a web server, the server replies with an HTTP response. The first line of that reply is the status line. This line includes the HTTP version, a three-digit status code, and a short reason phrase. For example:

HTTP/1.1 201 Created

Here, 201 is the status code and Created is the reason phrase. The number helps the browser know what happened. The text is for humans reading logs or tools.

What Happens After a Status Code is Sent

The status code sits inside the response header, not on the visible webpage. But browsers use this code to decide what to do next:

- A 200 means show the page

- A 3xx triggers a redirect to a new link

- A 401 may ask the user to log in

- A 404 shows a “not found” error page

Only one code is sent per response. The web server software picks the most fitting code based on what happened.

Who Defines and Controls Status Codes

The meaning of each HTTP status code is set by internet standards, written by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). These are stored in RFC documents. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) keeps the full list.

Tools like Apache, Nginx, and IIS follow these rules. Developers use code or server settings to send the right response:

- A 404 when a file is missing

- A 503 during server maintenance

While servers send the code, browsers or bots decide how to react based on protocol rules.

How did HTTP status codes evolve

HTTP status codes were not part of the original web protocol. In HTTP/0.9, released in 1991, servers sent only the page content—no headers, no codes. This made it hard to detect or manage errors. The first real status codes appeared in HTTP/1.0, defined by RFC 1945 in 1996. This version introduced essential codes like 200 OK, 404 Not Found, 500 Internal Server Error, and 302 Found.

Additions in HTTP/1.1 and beyond

The launch of HTTP/1.1 (RFC 2068 in 1997, later updated by RFC 2616 in 1999) expanded the set of codes. It added: 100 Continue, 303 See Other, 307 Temporary Redirect

These updates fixed confusion caused by how browsers handled 302 redirects. As the web matured, engineers proposed new codes to match new needs.

How new status codes are created

New HTTP status codes follow a public process managed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). Proposals are submitted through RFCs (Request for Comments). If accepted, the code becomes part of the official list.

Examples of later additions:

- 418 I’m a teapot – A humorous April Fools’ code

- 422 Unprocessable Entity – Used with WebDAV

429 Too Many Requests – Used to manage rate limits - 451 Unavailable For Legal Reasons – Used to show content blocked by law

Each approved code gets added to the IANA registry, which keeps the official list.

Non-standard and vendor-specific codes

Some servers use codes outside the official list. For example:

- Cloudflare uses 520 to 527 for network errors

- Microsoft IIS uses 440 Login Time-out

These are not standard and may confuse tools or browsers. Still, as long as the first digit shows the class (like 5xx for server errors), most clients handle them safely.

Role of IETF and IANA

The IETF defines what each code means. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) maintains the list and publishes updates. This structure keeps status codes consistent and trusted across the web.

How do HTTP status codes affect SEO

HTTP status codes are vital for how search engines understand, crawl, and index websites. When Googlebot or another crawler visits a page, the status code helps it decide whether to index the page, follow redirects, or slow down crawling. Correct use of these codes supports site health, visibility, and SEO performance.

How 2xx Codes Affect Indexing

2xx success codes, especially 200 OK, tell search engines that the content is available and the request worked. This does not guarantee indexing, but it allows the page to be considered. If the page is blank or shows an error message while still sending 200 OK, Google may treat it as a soft 404. These pages are not indexed because the content does not match the success code.

To avoid this, pages that do not exist should return a 404 Not Found or 410 Gone, not 200 OK. Pages returning 200 must offer clear, useful content.

Redirects and Search Signals

3xx codes signal that the page has moved.

- A 301 Moved Permanently tells Google to transfer link equity and update its index to the new page.

- A 302 Found suggests a temporary move. If the 302 lasts too long, Google may treat it like a 301 but not always.

- Google treats 301 and 308 as strong signals to switch indexing to the new URL.

- 302 and 307 are weak signals, so the old page may stay in the index.

Crawlers follow up to 10 redirects in a chain. Long chains should be avoided for SEO clarity.

Error Codes and Their Impact

4xx client errors tell Google the page is not available.

- 404 Not Found and 410 Gone are clear signs to remove a page from the index.

- These do not lower rankings for the whole site.

- 401 Unauthorized and 403 Forbidden also block indexing since crawlers cannot view the content.

- 429 Too Many Requests is seen as a crawl limit. Google slows down to reduce load, treating it like a 5xx server error.

5xx errors, such as 500 Internal Server Error or 503 Service Unavailable, signal server issues.

- If the error is short-term, Google waits before deindexing.

- A 503 code is useful during maintenance. Google understands it as temporary and will retry later.

- If 5xx errors last for days, Google may drop the pages from the index.

Soft 404 and Search Console Reporting

A soft 404 happens when a page looks empty or shows a not-found message, but the server still returns 200 OK. Google flags these in Search Console under Not indexed > Soft 404.

To fix it:

- Return a real 404 or 410

- Or add useful content to justify the 200 OK

This helps keep the index clean and avoids misleading search engines.

SEO Best Practices for Status Codes

Webmasters and SEO teams monitor status codes using tools like Google Search Console. Proper handling of each code helps ensure:

- Working pages return 200 OK

- Permanent changes use 301 redirects

- Temporary changes use 302 or 307

- Missing pages return 404 or 410

- Maintenance pages return 503

Avoid mistakes like sending 200 for broken pages, or using 302 when a 301 is correct. These errors confuse crawlers and may delay indexing or misplace SEO value.

Search Engine Trust and Technical SEO

Correct use of HTTP status codes helps search engines trust the site. Each response tells Google what the page is and how it should behave. When status codes match content accurately, search engines index more reliably and rank pages more confidently.

This improves:

- Technical SEO

- User experience

- Site structure clarity

- Crawl budget and page discovery

Reference

- https://developers.google.com/search/docs/crawling-indexing/http-network-errors

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Guides/Messages

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_HTTP_status_codes

- https://www.searchenginejournal.com/googles-john-mueller-clarifies-404-410-confusion-for-seo/513576/

- https://www.dotcom-monitor.com/wiki/knowledge-base/http-status-codes-list/

- https://nickberardi.com/world-of-http11-status-codes/

- https://http.dev/0.9

- https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-on-the-seo-impact-of-503-status-codes/514255/